Jeffrey Hamelman’s book ‘Bread’ is studded with recipes for fruit and nut breads made with different base doughs. This bread was a little late but definitely worth the wait. You can see what the other Mellow Bakers made of this one by clicking here. This month the random bread picker has thrown up a different variation again, a prune and hazelnut levain, which is possibly even more appealing, as I love French prunes.

April’s simple slow rising yeasted dough was stuffed full of roasted hazelnuts, dried figs, and scented with fresh rosemary and sweet cecily from the garden. Sweet cecily has a sweet aniseedy taste and I nibble at the seeds and fronds as I pass it growing in the garden, and occasionally add it to salads, I thought it would make a good substitute for fennel seeds, which didn’t appeal to me last time I put them in a bread.

I decided to use my tiny crop of hazelnuts from the red hazelnut shrub featured in the previous post. As I had no dried figs of my own, I bought some organic Turkish figs which were very juicy. I do have a fig tree, but it is young still  and I eat the figs that it manages to produce as they ripen. I can’t imagine having enough to dry for many years.

and I eat the figs that it manages to produce as they ripen. I can’t imagine having enough to dry for many years.

The dough was very firm and was quite nobbly with the whole nuts and the chunks of figs, so I decided to bake it in a closed pot as I wanted it to have a thin crust. The dough had its final proof inside the pot. I heated the oven up to 250 C, put the pot in cold (lid on) and then after twenty minutes took the pot out, took the lid off to a great whoosh of steam and put it back in the oven at 215 C for another twenty five minutes.

I think the bread could possibly have gone longer in the closed pot as it hadn’t fully risen when I took the lid off. However, it definitely gave the bread the thinner crust I was hoping for and I think the crumb is softer for that intense steaming too.

- Just delicious!

A couple of notes:

My hazelnuts are thinner skinned than the commercial ones, and despite being well toasted in the oven, they didn’t really want to rub off like the regular ones do. It didn’t matter at all.

I wasn’t sure whether to put the figs in whole or not, so I quartered them in the end and this seemed to produce a good sized piece. I was surprised at how good and juicy they remained after being baked, I was expecting them to go mushy or dry – never having put figs in a bread before. I was pleasantly surprised.

I put maybe a quarter of a teaspoon of finely snipped rosemary leaves in, less than called for, and the same of cecily seeds. I didn’t want to be overpowered by the aromatics and for my taste this was fine.

I upped the quantity of both nuts and figs as I am not making this bread commercially (see C’s comment below, it is indeed a lesson learnt from Dan Lepard!) I decided to put more in and the dough easily managed to absorb this as you can see from the pictures.

I made one loaf with the following, needing more water than the original recipe gives as my flours are very thirsty. Possibly I should have upped the water even more, as the nuts and figs absorb moisture from the dough.

- 250 grams very strong Canadian wholemeal flour (Waitrose brand)

- 250 gram strong bread flour (Shipton Mill)

- 370 grams warm water

- 10 grams seasalt

- 3/4 teaspoon dried yeast

- 100 grams of chopped figs

- 100 grams of toasted whole hazelnuts

- a little chopped rosemary and a scattering of sweet cecily seeds

- A firm dough full of goodies and another peek at the washing!

Mix all the ingredients together apart from the nuts and the figs, which you incorporate once the dough is mixed and has come together well. The dough has a long unhurried first prove of two and a half hours in a cool spot and then a second prove of about ninety minutes. Bake technique as above. Very hot to start with and then a cooler temperature for the second part of the bake.

Even though I adored the flavours and mouthfeel of this bread, with its surprising textures and tastes, I don’t know that I would make it that often as I can’t imagine turning it into sandwiches. Sliced fresh and spread with cold butter, it is sweet and rich; a meal in itself. It might work as rolls, but I would want to bake them covered somehow so as to keep the crust thin.

I made this bread yesterday and realised that I have in fact made it before when I first got my copy of Bread by Jeffrey Hamelman, before I started baking systematically through the book with the Mellow Bakers group. I love this bread and I can’t think why I haven’t made it again till now. So I am really pleased to see it turn up in

I made this bread yesterday and realised that I have in fact made it before when I first got my copy of Bread by Jeffrey Hamelman, before I started baking systematically through the book with the Mellow Bakers group. I love this bread and I can’t think why I haven’t made it again till now. So I am really pleased to see it turn up in I love the clean sourdough taste you get with this bread. I love the subtle texture and moistness that the flaxseed (linseed to us English) gives; I love the colour of the crust; I love the fact that the dough is easy to work and shape; I love the way it is easy to slash; and I love eating it. I am an unashamed rye fan, I think rye and sourdough go together beautifully, it is the taste of my childhood, the taste of family lunches and holidays. I am a rye sourdough soul through and through.

I love the clean sourdough taste you get with this bread. I love the subtle texture and moistness that the flaxseed (linseed to us English) gives; I love the colour of the crust; I love the fact that the dough is easy to work and shape; I love the way it is easy to slash; and I love eating it. I am an unashamed rye fan, I think rye and sourdough go together beautifully, it is the taste of my childhood, the taste of family lunches and holidays. I am a rye sourdough soul through and through. So here it is, from the pre-fermented magic of the starter; 20 grams of mature rye sourdough was all it took plus eighteen hours of cool time, to forming a mounded bowl of sourdough preferment, with its little holes peeping through the surface – a spoon cut through reveals the aeration:-

So here it is, from the pre-fermented magic of the starter; 20 grams of mature rye sourdough was all it took plus eighteen hours of cool time, to forming a mounded bowl of sourdough preferment, with its little holes peeping through the surface – a spoon cut through reveals the aeration:-  Then to the fun of mixing the mucilaginous gooey loveliness of well soaked linseeds. It all looks so unlikely somehow. Thanks to Carl and Choclette for your help with vocabulary and info today. From Choclette’s tweet ‘CT has come to the rescue on this one, the linseed mucilage is a polysaccharide – a mix of different sugars, so definitely carbohydrate’. I know budgies are supposed to sing when you feed them linseed. Don’t worry you can’t hear me tootling away on the internet (yet). Anyway it’s good for you!

Then to the fun of mixing the mucilaginous gooey loveliness of well soaked linseeds. It all looks so unlikely somehow. Thanks to Carl and Choclette for your help with vocabulary and info today. From Choclette’s tweet ‘CT has come to the rescue on this one, the linseed mucilage is a polysaccharide – a mix of different sugars, so definitely carbohydrate’. I know budgies are supposed to sing when you feed them linseed. Don’t worry you can’t hear me tootling away on the internet (yet). Anyway it’s good for you! It works, every time.

It works, every time. There is enough gluten provided by the very strong flour to support the rye component in the dough and I think the linseed juice adds magic glue too! The formula gives you enough dough to make either two big or one big and two little loaves which is what I did here.

There is enough gluten provided by the very strong flour to support the rye component in the dough and I think the linseed juice adds magic glue too! The formula gives you enough dough to make either two big or one big and two little loaves which is what I did here.

Don’t be put off making this bread by what it sounds like, the seeds aren’t crunchy in the bread, nor do they stick in your teeth. If you really don’t like rye, try adapting your regular sourdough formula to include a linseed soaker, or make

Don’t be put off making this bread by what it sounds like, the seeds aren’t crunchy in the bread, nor do they stick in your teeth. If you really don’t like rye, try adapting your regular sourdough formula to include a linseed soaker, or make

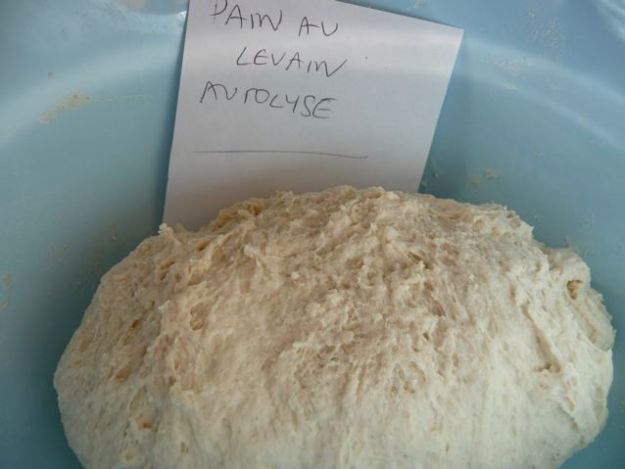

The main advantage as far as I can see in using a stiff levain to raise the bread is that a stiff levain takes up less space than a wet levain and ferments more slowly. It may well have a different flavour profile and other more complex characteristics but they are beyond me at the moment. The disadvantage is, as I have mentioned before, and as Melanie noted in a comment

The main advantage as far as I can see in using a stiff levain to raise the bread is that a stiff levain takes up less space than a wet levain and ferments more slowly. It may well have a different flavour profile and other more complex characteristics but they are beyond me at the moment. The disadvantage is, as I have mentioned before, and as Melanie noted in a comment

Proving times vary so much from week to week and it really is something that comes with experience. If you want to bake faster, you need to mix the dough fairly warm using warmer water, and have a warm proving place. It can be done; you get good bread with a milder flavour than you get from the longer proves. You can of course also use a little yeast to really speed the process up should you need to. It’s your bread, you make it the way that suits you!

Proving times vary so much from week to week and it really is something that comes with experience. If you want to bake faster, you need to mix the dough fairly warm using warmer water, and have a warm proving place. It can be done; you get good bread with a milder flavour than you get from the longer proves. You can of course also use a little yeast to really speed the process up should you need to. It’s your bread, you make it the way that suits you!